|

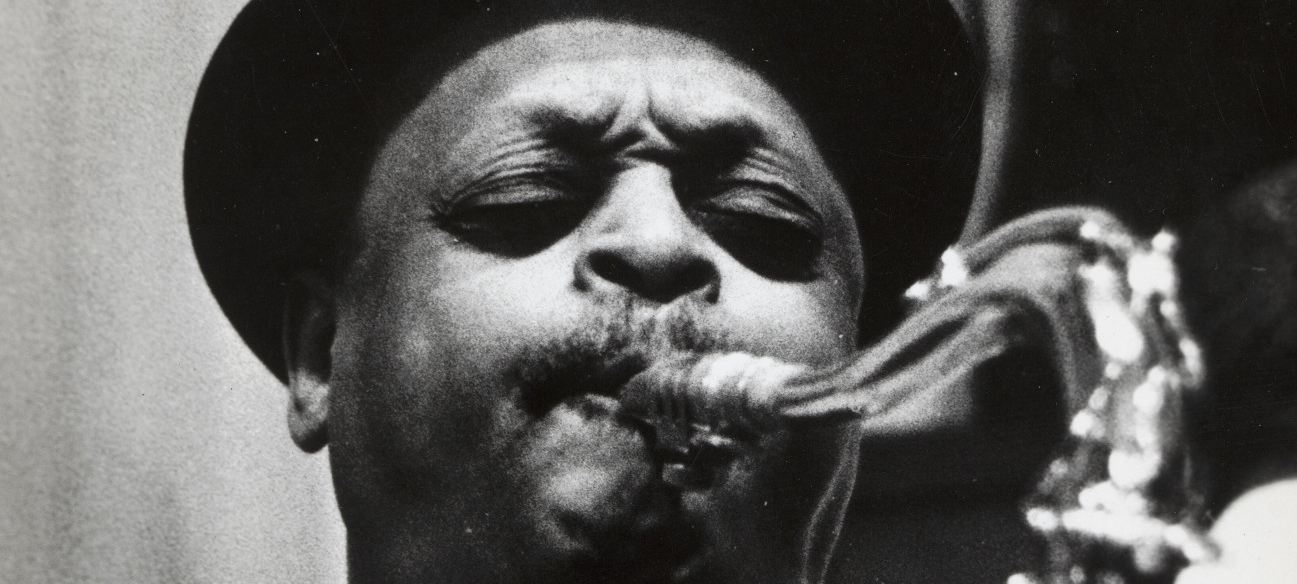

| Big Ben |

Jazz on Screen at the Barbican, Cinema 1, Sun 16 Nov 2025

Jazz In Exile – Big Ben: Ben Webster in Europe & Cecil Taylor à Paris + Intro by Ehsan Khoshbakht

This double bill offers two distinct portraits of ground-breaking American jazz musicians living and working in Europe, each navigating cultural displacement in their own unique way.

Big Ben: Ben Webster in Europe (1967) offers a lyrical, offstage portrait of a legendary saxophonist in Amsterdam. Ben Webster cooks, films his own life and reflects on the blues. In the film, his music and spirit explored through poetic visuals and intimate moments.

Cecil Taylor à Paris (1968) is a fierce, fast-cut portrait of an avant-garde pianist in Paris, rejecting the European canon and rooting his explosive sound in the Black American experience. The filmmaking mirrors the music’s energy, becoming a bold improvisation of its own.

Together, they reveal what it meant to be a Black jazz artist abroad, displaced not just by geography, but by culture, politics and sound.