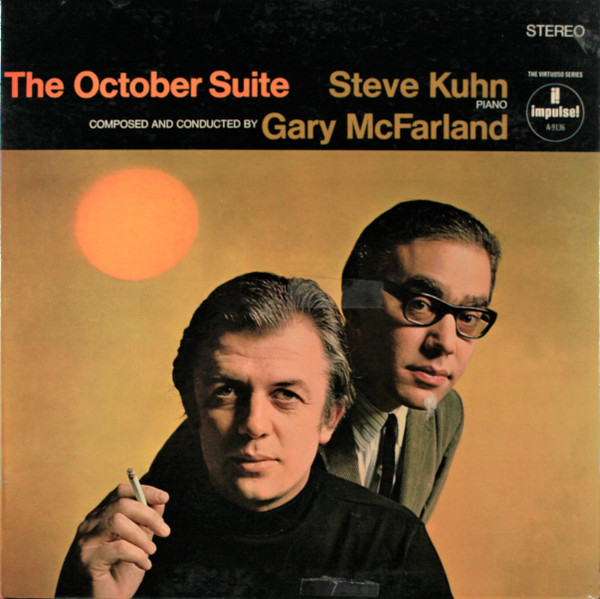

So far Steve Kuhn has primarily been heard in two contexts—as a sideman and as leader of a trio. This album, however, focuses on him as solo pianist in settings written specifically for him by Gary McFarland. For Gary the assignment was stimulating because, as he observed, he didn’t have to restrict himself to any particular idiom. Knowing the broad scope of Kuhn’s capacities, Gary felt free to try any approach he wanted in the confidence that Kuhn would respond resourcefully—and with individuality.

Steve, 28, was born in Brooklyn where he lived for nine years. After two and a half years in Chicago, his family moved to Newton, Massachusetts. He started studying piano at five and went on to major in music at Harvard where he received his B.A. The teacher who had the most influence on him, however, was Mrs. Margaret Chaloff, mother of the late Serge Chaloff. For years she has been a near-legged among musicians in the Boston area both for the quality of her teaching and herself.

In Boston, Kuhn worked with Serge Chaloff, had his own trio, and also functioned as part of a house rhythm section for such traveling stalwarts as Coleman Hawkins. He came to New York in 1959 and has worked since then with Kenny Dorham, Stan Getz, Art Farmer, and his own trio.

Recognizing Kuhn’s improvisatory strength, McFarland did not overwhelm him with decorative scoring. The writing for the accompanying instruments is sparse and therefore all the more effective. Most of Kuhn’s playing is improvised, and even the relatively few written sections for the piano have been embellished and otherwise changed in the course of the performance.

Except for One I Could Have Loved and Childhood Dreams, McFarland wrote these compositions for the album. One I Could Have Loved is the theme from the film, “13,” co-starring David Niven and Deborah Kerr. It’s a fragile, introspective song and is played here with exceptional collective sensitivity. Note, for one example, the subtlety of the interplay between Kuhn, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Marty Morell.

In this and the other tracks involving strings, McFarland’s writing is particularly evocative because he did not try to make the strings swing or otherwise take on jazz characteristics. Instead he wrote within the historical tradition of the instruments. He did the same with the woodwinds. Therefore, the “legitimate” sounds of the strings and the woodwinds continually provide a stimulating contrast to the jazz inflections and colorations of Kuhn, Carter and Morell. And the string and woodwind players, moreover, not being forced to adapt to another idiom, were able to play from strength. “The music,” Kuhn says, “lay perfectly for them.”

St. Tropez Shuttle is unusual in that it’s a bossa nova in 3/4 rather than the customary 4/4. Because of the scoring and Kuhn’s singular musical temperament and conception, it also explores a deeper range of mood than often occurs in a bossa nova performance.

The ardent romanticism of the string writing for Remember When is effectively complemented by the cooler but no less intense playing of Kuhn. The freshness, by the way, of McFarland’s string and woodwind sounds throughout the album is due in part to the fact that he first created the melodic lines for them and then allowed the melodies to determine the harmonic patterns. “It’s remarkable,” Kuhn adds, “how beautifully Gary’s writing for the strings and woodwinds came off when you consider he has not had much training in scoring for those instruments.” Clearly, in Gary’s case this lack of formal training freed him from pre-set conceptions of what could or could not be done and that’s why the results are so personal.

Traffic Patterns suggests the ceaseless, cross-hatched activity on urban streets, and again the classical textures of the woodwinds provocatively intersect with the bite and jazz-based thrust of Kuhn’s piano and the rhythm section. But since Kuhn is also classically trained, the contrast between his approach and that of the wind players is not so wide as to be jarring.

Childhood Dreams is based on a theme front, McFarland’s score for “13” and further illustrates the gentle lyricism which is central to much of McFarland’s work. He continues to develop as an uncommonly thoughtful melodist whose lines in retrospect have a sense of inevitability. And Kuhn again, through the discipline with which he handles his considerable musicianship, is able to probe and expand on those lines with absorbing structural inventiveness.

The final Open Highway, as have all the preceding tracks, invites—in fact, compels—the listener to create his own images from memory and desire. And the album as a whole allows the expressive skills of both Kuhn and McFarland to be experienced in new dimensions, dimensions particularly well suited to the essential musical concerns of both men. For McFarland these concerns are lucidity, melody and grace. With this instrumentation and the way he wrote for it, those qualities come through in deeper relief. For Kuhn, McFarland’s maturation as a writer helps channel his intensity and his searching musical intelligence into newly challenging directions.

Special note should also be taken of the work of Ron Carter and Marty Morell. Kuhn, who does not indulge in hyperbole, speaks of Carter’s intonation, sound and general musicianship as “incredible.” He adds: “Some of the things I did were anticipated by Ron at times and always were complemented by him. He was listening.” As for the 22-year-old Morell, Kuhn describes him as possessed of “an uncanny instinct. He’s one of those natural players, and in addition, he gets a marvelous sound from his instrument. Listen to those cymbals! He has the basic feeling I want in a drummer. The time is there, but it’s not piled down your throat. He’s flexible, and he too listens all the time.”

It is a unique combination of forces which produced this unconventional and yet immediately assimilable album. And the approach—letting the classical instruments function on their own terms simultaneously with jazzmen following their own idiom—may well stimulate other composers and performers from both fields to explore different combinations of equals. – Nat Hentoff, liner notes to The October Suite LP (Impulse! – AS-9136)

Musicians:

Steve Kuhn (piano), Ron Carter (bass), Marty Morell (drums)

Strings: Cello – Al Brown / Harp – Corky Hale / Viola – Charlie McCracken / Violin – Isador Cohen, Matt Raimondi /

Woodwind: Don Ashworth, Gerald Sanfino, Irving Horowitz, Joe Firrantello

No comments:

Post a Comment