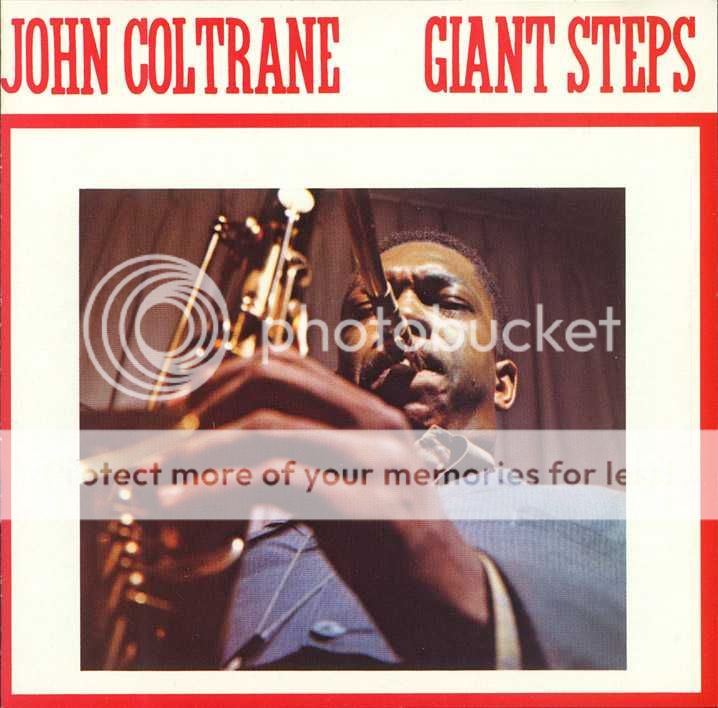

Along with Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane has become the most influential and controversial tenor saxophonist in modern jazz. He is becoming, in fact, more controversial and possibly more influential than Rollins. While it's true that to musicians especially, Coltrane's fiercely adventurous harmonic imagination is the most absorbing aspect of his developing style, the more basic point is that for many non-musician listeners, Coltrane at his best has an unusually striking emotional impact. There is such intensity in his playing that the string of adjectives employed by French critic Gerard Bremond in a Jazz-Hot article on Coltrane hardly seems at all exaggerated. Bremond called his playing "exuberant, furious, impassioned, thundering."

There is also, however, an extraordinary amount of sensitivity in Coltrane's work. Part of the fury in much of his playing is the fury of the search, the obsession Coltrane has to play all he can hear or would like to hear -- often all at once -- and yet at the same time make his music, as he puts it, "more presentable." He said recently, "I'm worried that sometimes what I'm doing sounds like just academic exercises, and I'm trying more and more to make it sound prettier." It

seems to me he already succeeds often in accomplishing both his aims, as sections of this album demonstrate.

This is the first set composed entirely of Coltrane originals. John has been writing since 1948. He was born in Hamlet, North Carolina, September 23, 1926. His father played several instruments, and interested his son in music. At 15, John learned E-flat alto horn and clarinet, and in high school, he switched to tenor. He studied. in Philadelphia at the Granoff Studios and the Ornstein School of Music, became a professional at 19, and played in a Navy band based in Hawaii from 1945-46. From 1947-49, he worked with Joe Webb (Big Maybelle was in the same entourage), King Kolax, Eddie Vinson and Howard McGhee. Charlie Parker had become a dominant influence on his playing.

He was on alto with the Dizzy Gillespie band in 1949, and after Dizzy disbanded, John returned to Philadelphia, discouraged and trying to find his own way in music. From 1952-53, he was with Earl Bostic, and then played with Johnny Hodges, Jimmy Smith, and Bud Powell.

He first joined Miles Davis from 1955-56. Miles regards Coltrane and Rollins as the two major modern tenors. "I always liked Coltrane." Miles said recently. "When he was with me the first time, people used to tell me to fire him. They said he wasn't playing anything. They also used to tell me to get rid of Philly Joe Jones. l know what I want though. I also .don't understand this talk of Coltrane being difficult to understand. What he does, for example, is to play five notes of a chord and then keep changing it around, trying to see how many different ways it can sound. It's like explaining something five different ways. And that sound of his is connected with what he's doing with the chords at any given time."

Miles encouraged Coltrane and also stimulated his harmonic thinking. In terms of writing as well, John feels he's learned from Miles to make sure that a song "is in the right tempo to be its most effective. He also made me go further into trying different modes in my writing." After two years with Miles? there was a period in 1957 with Thelonious Monk that Coltrane found unusually challenging. "I always had to be alert with Monk," he once said, "because if you didn't keep aware all the time of what was going on, you'd suddenly feel as if you'd stepped into an empty elevator shaft."

Coltrane worked briefly with a Red Garland quintet, then rejoined Miles, and has been with him ever since. He has nothing of his own in the Davis book at present, but he has devoted more and more of his time to composing. He is mostly self-taught as a writer, and generally starts his work at the piano. "I sit there and run over chord progressions and sequences, and eventually, I usually get a song -- or songs -- out of each little musical problem. After I've worked it out on the piano, I then develop the song further on tenor, trying to extend it harmonically." Coltrane tries to explain what drives him to keep stretching the harmonic possibilities of improvisation by saying, "I feel like I can't hear but so much in the ordinary chords we usually have going in the accompaniment. I just have to have more of a blueprint. It may be that sometimes I've been trying to force all those extra progressions into a structure where they don't fit, but this is all something I have to keep working on. I think too that my rhythmic approach has changed unconsciously during all this, and in time, it too should get as flexible as I'm trying to make my harmonic thinking."

In her analysis of Coltrane's style in the November and December, 1959, issues of The Jazz Review, pianist Zita Carno pointed out that Coltrane's range "is something to marvel at: a full three octaves upward from the lowest note obtainable on the horn (concert A-flat)...There are a good many tenor players who have an extensive range, but what sets Coltrane apart from the rest of them is the equality of strength in all registers, which he has been able to obtain through long, hard practice. His sound is just as clear, full and unforced in the topmost notes as it is down in the bottom." She describes his tone as "a result of the particular combination of mouthpiece and reed he uses plus an extremely tight embouchure" and calls it "an incredibly powerful, resonant and sharply penetrating sound with a spine-chilling quality."

Of the tunes, Coltrane says of Giant Steps that it gets its name from the fact that "the bass line is kind of a loping one. It goes from minor thirds to fourths, kind of a lopsided pattern in contrast to moving strictly in fourths or in half-steps." Tommy Flanagan's relatively spare solo and the way it uses space as part of its structure is an effective contrast to Coltrane 's intensely crowded choruses.

Cousin Mary is named for a cousin of Coltrane who is indeed called Mary. The song is an attempt to describe her. "She's a very earthy, folksy, swinging person. The figure is riff-like and although the changes are not conventional blues progressions, I tried to retain the flavor of the blues."

Countdown's changes are based in large part on Tune Up, but against that, Coltrane uses essentially the same sequence of minor thirds to fourths that characterizes Giant Steps. His solo here, and in the others as well, illustrates Zita Carno's point that Coltrane, for all he's trying to express in any given solo, has a remarkable sense of form.

Syeeda 's Song Flute has a particularly attractive line and is named for Coltrane's 10-year-old daughter. "When I ran across it on the piano," he says, "It reminded me of her because it sounded like a happy, child's song."

The tender Naima -- an Arabic name -- is also the name of John's wife. "The tune is built," Coltrane notes, "on suspended chords over an Eb pedal tone on the outside. On the inside-- the channel -- the chords are suspended over a Bb pedal tone." Here again is demonstrated Coltrane's more than ordinary melodic imagination as a composer and the deeply emotional strength of all his work, writing and playing.

There is a "cry" -- not at all necessarily a despairing one -- in the work of the best of the jazz players. It represents a man's being in thorough contact with his feelings, and being able to let them out, and that "cry" Coltrane certainly has.

Mr. P.C. is Paul Chambers who provides excellent support and thoughtful solos on the record as a whole and whom Coltrane regards as "one of the greatest bass players in jazz. His playing is beyond what I could say about it. The bass is such an important instrument, and has so much to do with how a group and a soloist can best function that I feel very fortunate to have had him on this date and to have been able to work with him in Miles' band so long." Tom Dowd's engineering, incidentally, has caught Paul's sound as well as it's ever been heard on records, and for an insight into the importance of the bass's function, it might be valuable to go through the record once, paying attention primarily to Paul. Also worth noting is the steady, generally discreet drumming of Arthur Taylor and Jimmy Cobb throughout.

What makes Coltrane one of the most interesting jazz players is that he's not apt to ever stop looking for ways to perfect what he's already developed and also to go beyond what he knows he can do. He is thoroughly involved with plunging as far into himself and the expressive possibilities of his horn as he can. As Zita Carno wrote, "the only thing to expect from John Coltrane is the unexpected." I'd qualify that dictum by adding that one quality that can always be expected from Coltrane is intensity. He asks so much of himself that he can thereby bring a great deal to the listener who is also willing to try relatively unexplored territory with him.

There is also, however, an extraordinary amount of sensitivity in Coltrane's work. Part of the fury in much of his playing is the fury of the search, the obsession Coltrane has to play all he can hear or would like to hear -- often all at once -- and yet at the same time make his music, as he puts it, "more presentable." He said recently, "I'm worried that sometimes what I'm doing sounds like just academic exercises, and I'm trying more and more to make it sound prettier." It

seems to me he already succeeds often in accomplishing both his aims, as sections of this album demonstrate.

This is the first set composed entirely of Coltrane originals. John has been writing since 1948. He was born in Hamlet, North Carolina, September 23, 1926. His father played several instruments, and interested his son in music. At 15, John learned E-flat alto horn and clarinet, and in high school, he switched to tenor. He studied. in Philadelphia at the Granoff Studios and the Ornstein School of Music, became a professional at 19, and played in a Navy band based in Hawaii from 1945-46. From 1947-49, he worked with Joe Webb (Big Maybelle was in the same entourage), King Kolax, Eddie Vinson and Howard McGhee. Charlie Parker had become a dominant influence on his playing.

He was on alto with the Dizzy Gillespie band in 1949, and after Dizzy disbanded, John returned to Philadelphia, discouraged and trying to find his own way in music. From 1952-53, he was with Earl Bostic, and then played with Johnny Hodges, Jimmy Smith, and Bud Powell.

He first joined Miles Davis from 1955-56. Miles regards Coltrane and Rollins as the two major modern tenors. "I always liked Coltrane." Miles said recently. "When he was with me the first time, people used to tell me to fire him. They said he wasn't playing anything. They also used to tell me to get rid of Philly Joe Jones. l know what I want though. I also .don't understand this talk of Coltrane being difficult to understand. What he does, for example, is to play five notes of a chord and then keep changing it around, trying to see how many different ways it can sound. It's like explaining something five different ways. And that sound of his is connected with what he's doing with the chords at any given time."

Miles encouraged Coltrane and also stimulated his harmonic thinking. In terms of writing as well, John feels he's learned from Miles to make sure that a song "is in the right tempo to be its most effective. He also made me go further into trying different modes in my writing." After two years with Miles? there was a period in 1957 with Thelonious Monk that Coltrane found unusually challenging. "I always had to be alert with Monk," he once said, "because if you didn't keep aware all the time of what was going on, you'd suddenly feel as if you'd stepped into an empty elevator shaft."

Coltrane worked briefly with a Red Garland quintet, then rejoined Miles, and has been with him ever since. He has nothing of his own in the Davis book at present, but he has devoted more and more of his time to composing. He is mostly self-taught as a writer, and generally starts his work at the piano. "I sit there and run over chord progressions and sequences, and eventually, I usually get a song -- or songs -- out of each little musical problem. After I've worked it out on the piano, I then develop the song further on tenor, trying to extend it harmonically." Coltrane tries to explain what drives him to keep stretching the harmonic possibilities of improvisation by saying, "I feel like I can't hear but so much in the ordinary chords we usually have going in the accompaniment. I just have to have more of a blueprint. It may be that sometimes I've been trying to force all those extra progressions into a structure where they don't fit, but this is all something I have to keep working on. I think too that my rhythmic approach has changed unconsciously during all this, and in time, it too should get as flexible as I'm trying to make my harmonic thinking."

In her analysis of Coltrane's style in the November and December, 1959, issues of The Jazz Review, pianist Zita Carno pointed out that Coltrane's range "is something to marvel at: a full three octaves upward from the lowest note obtainable on the horn (concert A-flat)...There are a good many tenor players who have an extensive range, but what sets Coltrane apart from the rest of them is the equality of strength in all registers, which he has been able to obtain through long, hard practice. His sound is just as clear, full and unforced in the topmost notes as it is down in the bottom." She describes his tone as "a result of the particular combination of mouthpiece and reed he uses plus an extremely tight embouchure" and calls it "an incredibly powerful, resonant and sharply penetrating sound with a spine-chilling quality."

Of the tunes, Coltrane says of Giant Steps that it gets its name from the fact that "the bass line is kind of a loping one. It goes from minor thirds to fourths, kind of a lopsided pattern in contrast to moving strictly in fourths or in half-steps." Tommy Flanagan's relatively spare solo and the way it uses space as part of its structure is an effective contrast to Coltrane 's intensely crowded choruses.

Cousin Mary is named for a cousin of Coltrane who is indeed called Mary. The song is an attempt to describe her. "She's a very earthy, folksy, swinging person. The figure is riff-like and although the changes are not conventional blues progressions, I tried to retain the flavor of the blues."

Countdown's changes are based in large part on Tune Up, but against that, Coltrane uses essentially the same sequence of minor thirds to fourths that characterizes Giant Steps. His solo here, and in the others as well, illustrates Zita Carno's point that Coltrane, for all he's trying to express in any given solo, has a remarkable sense of form.

Syeeda 's Song Flute has a particularly attractive line and is named for Coltrane's 10-year-old daughter. "When I ran across it on the piano," he says, "It reminded me of her because it sounded like a happy, child's song."

The tender Naima -- an Arabic name -- is also the name of John's wife. "The tune is built," Coltrane notes, "on suspended chords over an Eb pedal tone on the outside. On the inside-- the channel -- the chords are suspended over a Bb pedal tone." Here again is demonstrated Coltrane's more than ordinary melodic imagination as a composer and the deeply emotional strength of all his work, writing and playing.

There is a "cry" -- not at all necessarily a despairing one -- in the work of the best of the jazz players. It represents a man's being in thorough contact with his feelings, and being able to let them out, and that "cry" Coltrane certainly has.

Mr. P.C. is Paul Chambers who provides excellent support and thoughtful solos on the record as a whole and whom Coltrane regards as "one of the greatest bass players in jazz. His playing is beyond what I could say about it. The bass is such an important instrument, and has so much to do with how a group and a soloist can best function that I feel very fortunate to have had him on this date and to have been able to work with him in Miles' band so long." Tom Dowd's engineering, incidentally, has caught Paul's sound as well as it's ever been heard on records, and for an insight into the importance of the bass's function, it might be valuable to go through the record once, paying attention primarily to Paul. Also worth noting is the steady, generally discreet drumming of Arthur Taylor and Jimmy Cobb throughout.

What makes Coltrane one of the most interesting jazz players is that he's not apt to ever stop looking for ways to perfect what he's already developed and also to go beyond what he knows he can do. He is thoroughly involved with plunging as far into himself and the expressive possibilities of his horn as he can. As Zita Carno wrote, "the only thing to expect from John Coltrane is the unexpected." I'd qualify that dictum by adding that one quality that can always be expected from Coltrane is intensity. He asks so much of himself that he can thereby bring a great deal to the listener who is also willing to try relatively unexplored territory with him.

No comments:

Post a Comment